Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is common. It is estimated that if we lived long enough, all of us would eventually get a prostate cancer.

However, only one man in nine in Ireland is diagnosed with this cancer in his lifetime, and only skin cancer is more commonly found. Since we all die eventually, most of us will die from some other reason and will never know we had prostate cancer.

It is not a uniform type of cancer, and it affects each of us in a different way. Thankfully most forms are relatively harmless and will never bother us, but not all.

Prostate cancer is never diagnosed until you have had a prostate biopsy.

What is Prostate cancer?

In our bodies, the growth of all our cells is controlled and monitored.

As they eventually die, they are replaced in an orderly fashion, but if this is disrupted and they are replaced abnormally a cancer can develop. Cancers can appear anywhere in the body, and for some unexplained reason our prostate is one of the most likely.

What causes Prostate cancer?

Unfortunately, we don’t know. That is a fact. What we do know is that some men are more likely to get it than others.

Men who are more susceptible to prostate cancer include:

- Older men. The older we are the more likely we will get a cancer. It is estimated that 80% of 80 year old men will have a cancer, but it will affect very few of them. It is very uncommon below the age of 50, but not unknown.

- Family history. Prostate cancers do run in families.

- Race. Black men are more at risk than Caucasians.

Can I prevent Prostate cancer?

Realistically, no. There is some evidence that there may be lifestyle elements in cancer risk, but this is unproven.

Symptoms of Prostate Cancer

Most prostate cancers have no symptoms, and are detected either by chance or from getting a check up. This is because the majority are situated in the back of the gland, in the area called the ‘peripheral zone’, and they can become fairly large before being noticed.

Most prostate cancers have no symptoms, and are detected either by chance or from getting a check up. This is because the majority are situated in the back of the gland, in the area called the ‘peripheral zone’, and they can become fairly large before being noticed.

Most of the things we notice when our prostate causes a problem come either from a non cancerous enlargement of the gland, or from an inflammation, which is also non cancerous. In the course of these being investigated a coincidental and coexisting cancer is detected, but it is only rarely the cause of the symptoms.

When a prostate cancer does produce symptoms, such as pain or blood in the urine, it is now more difficult to treat it, so early detection is the ideal.

How is Prostate cancer diagnosed?

Prostate cancer is diagnosed by a series of tests carried out by a doctor including:

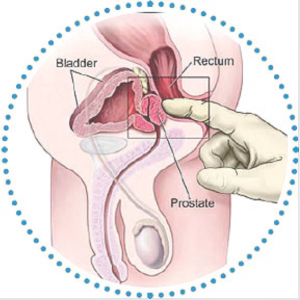

- Digital Rectal Examination (DRE). This is totally painless, and means that your doctor puts a gloved and lubricated finger gently into your rectum, and feels the prostate gland which lies directly in front of the back passage. Few cancers are diagnosed this way, but are suspected, and if your doctor feels an abnormality you will be referred for further tests.

- PSA test – a blood test primarily used to screen for prostate cancer. Further information available here.

It all depends. Prostatic cancer is generally suspected for three reasons:

1. An abnormal Digital Rectal Examination (DRE).

2. An abnormal PSA test.

3. A combination of both.

Abnormal DRE

If your doctor tells you that your prostate feels abnormal, and that a cancer is a possibility, you will generally be referred to a specialist, either in a designated Prostate Cancer Centre or to a urologist with expertise in prostate cancer. This generally happens no matter what your PSA test says.

Abnormal PSA test

It depends on the PSA level and what turns up on a DRE. If your PSA is only slightly raised, and DRE is normal, the best course is usually to do nothing except repeat the PSA. When that should be depends on how high it is.Rapid Access Prostate Clinics recommend a wait of at least 6 weeks before re-testing.Six months can be considered reasonable by some if the PSA is only slightly raised and often the PSA is lower with the next result. If it is the same, it can be done again 6 months later and so on. You will be referred on if it is rising, especially if it is rising significantly.If prostate infection is suspected, the best action is to take an adequate course of antibiotic – usually 4 weeks – and then repeat the PSA. Often it has returned to normal. Panic over. If it is still raised you will be referred to a specialist.

Abnormal PSA and DRE

Most GPs would recommend referral either to a Rapid Access Clinic or to a specialised urologist. There is no very immediate hurry – it does not need to be the same week. Even the very worst prostate cancers are slow growing compared to other cancers, but of course we want to know. That’s human nature. It also gives us time, in a modern age of information accessibility, to inform ourselves about the disease.

These rapid access prostate clinics are located in each of the following eight designated cancer centres:

Beaumont Hospital Dublin 9

St. James Hospital Dublin

St. Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin 4

Mater University Hospital Dublin 7

Cork University Hospital

Galway University Hospital

Midwestern Regional Hospital Limerick

Waterford Regional Hospital

Private rapid access prostate clinics

Mater Hospital Dublin.

Mercy Hospital Cork

Bon Secours Cork

If you have been referred, either to a Rapid Access Prostate Clinic or to a urologist, there is a standard set of investigations performed to assess the possible problem. These initial tests usually include;

• Digital Rectal Examination or DRE.

• Ultrasound examination of prostate, or TRUS.

• MRI scans of your pelvis.

• Biopsy of your prostate.

• Possibly a Bone Scan.

Digital Rectal Examination or DRE

This will probably have been done already by your GP but your urologist will always want to check too. This involves examining your prostate with a finger slowly and carefully inserted up the back passage.A glove is always used, along with lots of lubricating jelly. While this may be embarrassing, it is painless and fairly quick. Your urologist can estimate the size of the prostate, and whether there are any suspicious bumps. Most prostate cancers – but not all – come from the back of the prostate (which literally touches the back passage) and can be felt there.

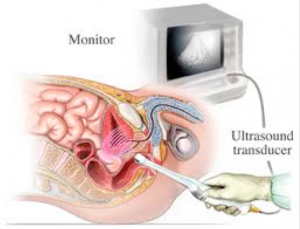

Ultrasound examination of prostate, or TRUS

Unfortunately, because our prostates lie very low in the pelvis, they are difficult to visualise with an ultrasound from the front, so they are viewed from the back. This means using an ultrasound probe inserted up the back passage.These probes are thin – not much larger than a finger. Because our prostate and our rectum (back passage) touch each other, the probe gets an excellent image of the prostate, and an area with a possible cancer may be identified. In many cases, however, this examination can seem normal.

MRI scans of your pelvis.

The importance and usefulness of having an MRI scan to check not just the prostate itself but also the tissues nearby is increasingly being appreciated.MRI can tell if the prostate looks normal, and maybe avoid an invasive biopsy, or if an abnormal area is seen in the prostate it will help the surgeon know which part need to be biopsied.This is very important. Although most prostate cancers are in the back of the gland, which can be accessed by the traditional biopsy route, some 20% are in the front of the gland, and can only be accessed and tested for by a new procedure called a transperineal biopsy.Unfortunately at present most MRI scans of prostate are performed only in private hospitals and clinics.

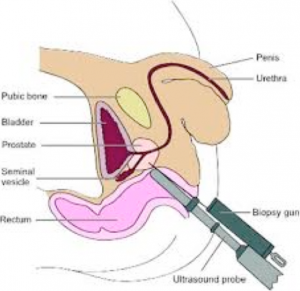

TRUS guided prostate biopsy

This can be done in at the same time as the ultrasound examination, using the same instrument with a biopsy needle attached.Biopsy means taking a small sample of tissue so that it can be examined under a microscope. A local anaesthetic injection is used, or else you may be knocked out with a general anaesthetic. This can be discussed with the urologist.If a suspicious area is notice with the ultrasound then that area will be biopsied, but more often the ultrasound seems normal. Then, under ultrasound guidance, 10-12 biopsy samples are taken using an identical pattern for all of us – rather like a clock with numbers and a sample taken from each. These samples are sent off to the lab to be examined.You are always given some strong antibiotics to take, to reduce the risk of infection.The result of the biopsies takes at least 2 weeks, so you will need a second appointment to be told the news.While embarrassing and uncomfortable, it should not be a painful experience. However, prostate biopsy is not without its problems.These include:

- Infection. In spite of use of antibiotics, up to 2% of us having prostate biopsy will develop a prostate infection – sometimes a serious one that may need hospital admission and treatment.

- Bleeding. It is normal to get some blood in the urine, faeces and semen, but occasionally a serious bleed needing hospital treatment can occur.

- It is unusual, but biopsy can cause the prostate to swell and block off passing urine. If this happens we will need to have a tube called a catheter inserted up through the penis into the bladder to relieve the blockage.

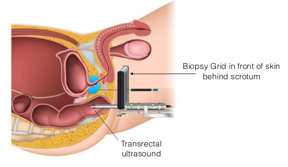

Trans Perineal Biopsy

Trans Perineal Biopsy

Prostate biopsy has traditionally been performed via the rectum (transrectal ultrasound-guided – TRUS – biopsy).Whilst TRUS biopsy is still the standard approach for an initial prostate biopsy, it has potential drawbacks, including:

- The front part of the prostate may not be accessible to biopsy via the rectum. Although prostate cancer arises less commonly in this region, it could be missed by a TRUS biopsy.

- Secondly, the TRUS biopsy has a small but significant risk of serious infection. This is due to passage of the biopsy needle through the rectal wall. The perineum is the part of the body between the scrotum and anus. A transperineal biopsy of the prostate is carried out via the skin overlying this area. Imaging is obtained by an ultrasound probe passed into the rectum, and biopsy needles are passed parallel to this, allowing access to all aspects of the gland. This allows improved sampling, particularly in men who have had a previous negative TRUS biopsy but whose PSA continues to rise.The transperineal biopsy has the additional advantage of a much lower risk of infection, as the skin of the perineum can be easily disinfected prior to the procedure. A higher number of tissue samples are taken by transperineal biopsy.There are some disadvantages:

- A general anaesthetic is necessary

- It takes much longer to perform than TRUS

- Some of the samples are taken from areas closer to the urethra, which runs through the prostate. As a result, there appears to be a higher risk of temporary voiding difficulty, including urinary retention.

- Not all clinics have access to this procedure.

Result of the prostate biopsyNormally 18-30 biopsy samples are taken, and about 2 weeks later the results are available. At that visit the urologist will tell you the results of the tests, along with some numbers called the Gleason Score. This is the internationally scoring or rating of severity of a prostate cancer.

Normal biopsy samples are taken, and about 2 weeks later the results are available. At that visit the urologist will tell you the results of the tests, along with some numbers called the Gleason Score. This is the internationally scoring or rating of severity of a prostate cancer.

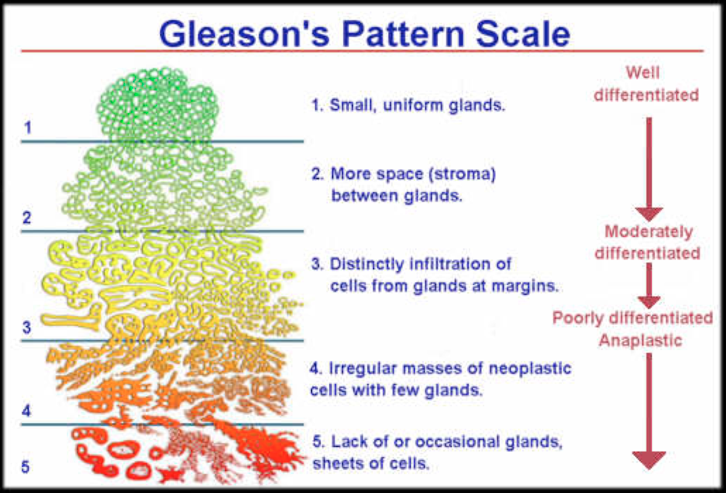

Prostate cancer cells in your biopsy samples are given a grade. This tells you how aggressive the cancer is – in other words, how likely it is to grow and spread outside the prostate.

When cancer cells are seen under the microscope, they have different patterns, depending on how quickly they’re likely to grow. This is called the Gleason grade.

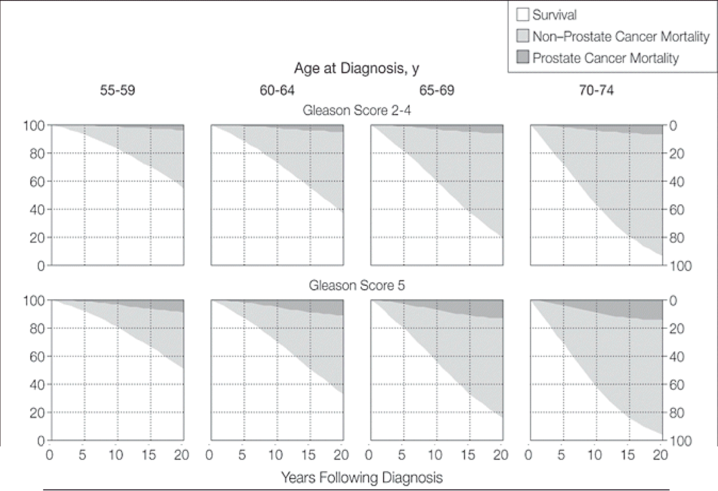

For each biopsy sample, pathologists examine the most common tumor pattern and the second most common pattern. Each is given a grade of 1 to 5, the higher numbers indicating more severity. These grades are then combined to create the Gleason score. For example, if the most common tumor pattern is grade 3, and the next most common tumor pattern is grade 4, the Gleason score is 3 plus 4, or 7. Because the first number represents the majority of abnormal cells in the biopsy sample, a 3 + 4 is considered less aggressive than a 4 + 3. Combined scores of 8 or higher are the most aggressive cancers. Those under 6 have a better prognosis. Gleason scores of 1 and 2 are not considered to be cancers.

What does the Gleason score mean?

The higher the Gleason score, the more aggressive the cancer, and the more likely it is to spread.

- 3+3 – All of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow slowly.

- 3+4 – Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow slowly. There were some cancer cells that look more likely to grow at a more moderate rate.

- 4+3 – Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow at a moderate rate. There were some cancer cells that look likely to grow slowly.

- 4+4 – All of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow at a moderately quick rate.

- 4+5 – Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow at a moderately quick rate. There were some cancer cells that are likely to grow more quickly.

- 5+4 – Most of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow quickly.

- 5+5 – All of the cancer cells found in the biopsy look likely to grow quickly.

What happens next?

This depends, mainly upon the Gleason Score, how healthy you (the patient) are, and whether you want any treatment at all. This will be discussed with your urologist.

With a firm diagnosis of cancer, your urologist will probably want to have a scan of your pelvis – usually an MRI scan – to check if the cancer has spread from the prostate to any nearby organs, or to other glands in the pelvis. You may also be sent for a different test called a Bone Scan. Prostatic cancers may spread to our bones – especially the spine – and these will show on a bone scan if present. When the result of these scans are available, then both of you are in a better position to discuss treatment options.

Your urologist will tell you what stage your prostate cancer is at, and different treatment options are offered for different stages.

Prostate Cancer Staging

Staging is a way of recording how far the cancer has spread. The most common method is the TNM (Tumour-Nodes-Metastases) system.

Staging is usually assessed after prostate biopsy, MRI imaging, and perhaps bone scan.

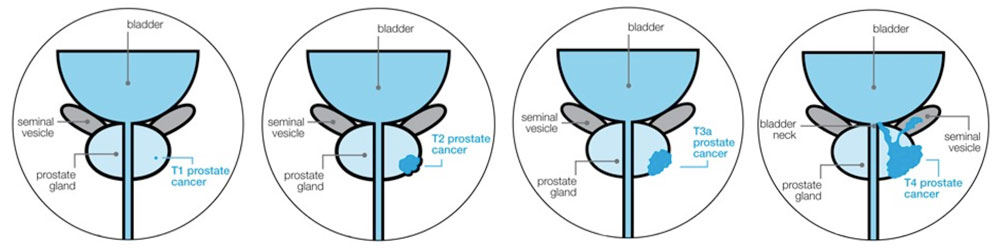

- The T stage shows how far the cancer has spread in and around the prostate.

- The N stage shows whether the cancer has spread to the pelvic lymph nodes.

- The M stage shows whether the cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

T Stage

The T stage shows how far the cancer has spread in and around the prostate.

T1 prostate cancer

The cancer can’t be felt or seen on scans, and can only be seen under a microscope – very localised prostate cancer.

T2 prostate cancer

The cancer can be felt on DRE, or seen on scans, but is still contained inside the prostate – localised prostate cancer.

T3 prostate cancer

The cancer can be felt or seen breaking through the capsule of the prostate – locally advanced prostate cancer.

- T3a The cancer has broken through the capsule of the prostate but has not spread to the seminal vesicles

- T3b The cancer has spread to the seminal vesicles.

T4 prostate cancer

The cancer has spread to nearby organs, such as the neck of the bladder, back passage, pelvic wall or lymph nodes – locally advanced prostate cancer.

N Stage prostate cancer

The N stage shows whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes near the prostate – a common place for prostate cancer to spread to. An MRI (or CT) scan is used to find out your N stage. The possible N stages are:

- NX The lymph nodes were not looked at, or the scans were unclear.

- N0 No cancer can be seen in the lymph nodes.

- N1 The lymph nodes contain cancer.

If your scans suggest that your cancer has spread to the lymph nodes (N1), it may either be treated as locally advanced or advanced prostate cancer. This may depend on several things, such as how far it has spread (M stage).

M Stage prostate cancer

The M stage shows whether the cancer has spread (metastasized) to other parts of the body, usually the bones. A bone scan is needed to find out the M stage.

- MX The spread of the cancer wasn’t looked at, or the scans were unclear.

- M0 The cancer hasn’t spread to other parts of the body.

- M1 The cancer has spread to other parts of the body. M1 is farther subdivided into three classes

1a. To non-local lymph nodes.

1b. To bone.

1c. To other sites.

Prostate Cancer Treatment

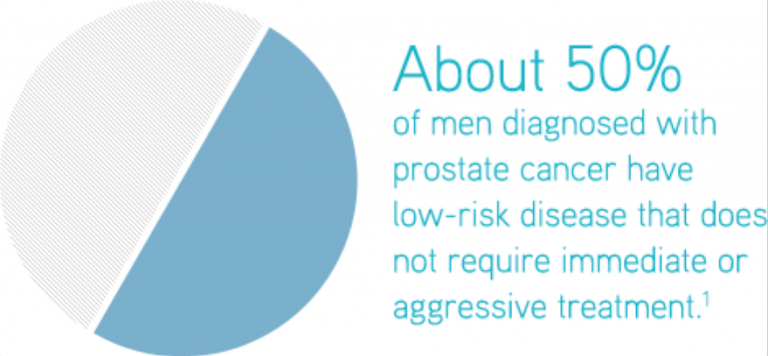

Most of us with prostate cancer will die with our cancer, not because of it. Even if a cancer is aggressive, or has spread, it will generally respond to conventional treatment. This may not cure the cancer, but will give a good quality of life for a considerable time.

Compared to some other cancers, most prostate cancers are slow to grow and slow to spread, and there is generally no urgency in beginning treatment. This gives us time to discuss all aspects of management with our medical teams, and to decide which treatment –if any at all – we wish to pursue.

Treatment Choices

- There are a number of different treatments, and choice of treatment will depend upon a number of factors including;

- Type and staging of the cancer.

- Your general health and life expectancy. A very fit 55 years old will decide a very different treatment than an unwell 75 years old.

- Facilities available. Not all treatment options may be available.

- Accessibility. This mainly relates to radiotherapy treatment, which can be fairly prolonged, and may not suit someone living far away from the facility.

- Personal choice. Some of us are terrified of surgery, and will not consider it an option.

- Affect on our sex life. Some treatments affect it more than others and might not be considered.

- Personal choice, having weighed up pros and cons.

- Advice of our medical teams. They are the experts. Not always right, but most of the time they are. We should listen, even if we don’t agree.

- Expense. Not all treatments are available through public health services. Unjust but true.

Types of Non-Surgical Treatment

Active Surveillance

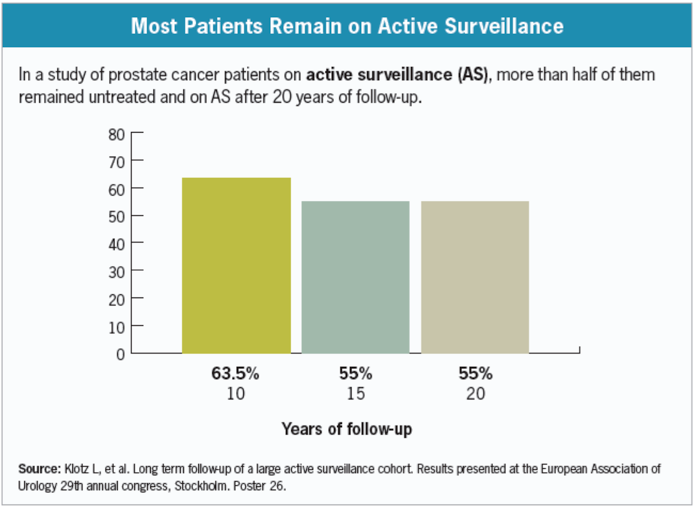

This is a way of monitoring slow-growing prostate cancer, contained within the prostate, rather than treating it straight away. The aim is to avoid unnecessary treatment, or delay treatment and the possible side effects unless there are signs the cancer may be growing.

It may seem strange not to have treatment, but some types of prostate cancer are slow-growing and may not cause any problems in your lifetime. You might never need any treatment.

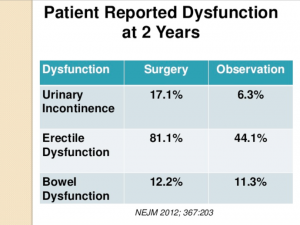

Treatments for prostate cancer can cause side effects, such as leaking urine, difficulty getting and keeping an erection, and bowel problems. For some of us these side effects may have a big impact on our daily lives.

If you decide to go on active surveillance, you won’t have any treatment unless your tests show that your cancer may be growing – so you’ll avoid or delay these side effects. However, if there are signs your cancer may be growing, you will be offered treatment which aims to cure it.

It usually involves more regular hospital tests, such as follow up DRE examinations, PSA tests, prostate biopsies and MRI scans. Active surveillance may also be suitable for those of us with cancer that may be more likely to spread (medium risk), but who want to avoid or delay treatment.

Advantages

- As you won’t have treatment while you’re on active surveillance, you’ll avoid the side effects of treatment.

- Active surveillance doesn’t interfere with your everyday life as much as treatment might do.

- If tests show that the cancer might be growing, there are treatments available that aim to cure it.

Disadvantages

- You will need to have more prostate biopsies.

- There is a chance that the cancer might grow more quickly than expected and become harder to treat.

- Your general health could change, which might make some treatments unsuitable for you if you did need them.

What is usually involved?

Each hospital has its own set of guidelines, but most involve

- A PSA test every three months to six months.

- A Digital Rectal Examination (DRE) every six to 12 months.

- A repeat prostate biopsy about 6-12 months after you were diagnosed, and then every few years.

- An MRI scan of your PSA or DRE suggest the cancer is growing. Some clinics do this routinely.

If the results of the tests show your cancer has grown, you’ll be offered treatment which aims to cure the cancer.

Some of us on active surveillance have treatment because the tests show the cancer has changed. But some of us may decide we want to have treatment even though there are no signs of any changes. This is often because we are worried the cancer will spread. If you decide you do want treatment, speak to your doctor or nurse about the options.

Are there any risks with active surveillance?

There’s always a small chance that changes might be missed – the cancer has spread outside the prostate before being picked up, and treatment might not be able to get rid of it. However, research shows that active surveillance is a safe way of avoiding unnecessary treatment for men with low risk prostate cancer.

There’s also a chance that your general health could change, which would make some treatments unsuitable for you if the cancer did grow. For example, if you were to develop new heart problems, you might not be able to have surgery, as an operation might not be safe.

Current guidelines for Active Surveillance from the UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (N.I.C.E.)

| Timing | Tests |

| At enrolment in active surveillance | Multiparametric MRI if not previously performed |

| Year 1 of active surveillance | Every 3-4 months: measure PSA (prostate-specific antigen) Throughout active surveillance: monitor PSA kinetics Every 6-12 months: DRE (digital rectal examination) At 12 months: prostate rebiopsy |

| Years 2-4 of active surveillance | Every 3-6 months: measure PSA Throughout active surveillance: monitor PSA kinetics3 Every 6-12 months: DRE4 |

| Year 5 and every year thereafter until active surveillance ends | Every 6 months: measure PSA Throughout active surveillance: monitor PSA kinetics3 Every 12 months: DRE4 |

Watchful waiting is a way of monitoring prostate cancer that isn’t causing any symptoms or problems. The aim is to keep an eye on the cancer over the long term, and avoid treatment unless you get symptoms. Prostate cancer is often slow growing and may not cause any problems or symptoms in your lifetime. And many treatments for prostate cancer can cause side effects. For some men these side effects may be long-term and may have a big impact on their daily lives.

If you decide to go on watchful waiting, you won’t have any treatment unless you get symptoms, so you’ll avoid these side effects. Many men on watchful waiting never need any treatment for their prostate cancer. But for some men, their cancer may grow more quickly than expected.

If your cancer does grow more quickly than expected and you get symptoms, you can start treatment to control the cancer and help manage symptoms.

Who may be suitable for watchful waiting?

Watchful waiting may be for you if your prostate cancer isn’t causing any symptoms or problems, and:

- you have other health problems which mean you might not be fit enough for treatments such as radiotherapy or surgery, or

- your type of prostate cancer isn’t likely to cause any problems during your lifetime or shorten your life.

It’s also important that you’ve discussed other treatment options with your doctor and you’re happy to go on watchful waiting.

Advantages

Advantages

- As you won’t have treatment while you’re on watchful waiting, you’ll avoid any side effects of treatment.

- You won’t need to have invasive tests such as regular prostate biopsies.

- There are treatments available to control your cancer and manage your symptoms if you start to get symptoms. But many men never need treatment at all.

Disadvantages

- There is a chance that the cancer may change and grow more quickly than expected. If this happens you can start treatment.

- Some men may worry about their cancer growing and about getting symptoms. Also family members may worry about their loved one and find it hard to understand why he is not having treatment.

What does watchful waiting involve?

If you’re on watchful waiting you will have tests to monitor your cancer. You won’t have any treatment unless you get symptoms.

You’ll normally have a PSA test at your GP surgery or hospital clinic every 3 to 12 months. You might also have digital rectal examinations (DRE) tests. You probably won’t need to have any more prostate biopsy. If any changes are picked up by these tests or you have any new or different symptoms, then you may be referred back to your hospital.

What is the difference between active surveillance and watchful waiting?

Watchful waiting is often confused with active surveillance. The aim of both is to avoid having unnecessary treatment, but there are key differences.

Active surveillance

- If you need treatment, it will aim to cure the cancer.

- It is suitable for some men with cancer that is contained in the prostate (localised cancer).

- It usually involves more regular hospital tests, such as DRE examinations, PSA tests, prostate biopsies and in some centres MRI scans.

Watchful waiting

- If you need treatment, it will aim to control the cancer rather than cure it.

- It’s generally suitable for a man with significant health problems who may be less able to cope with other treatments, and whose cancer may never cause a problem in his lifetime

- It usually involves fewer tests than active surveillance. These check-ups usually take place at the GP surgery rather than at the hospital.

All parts of our bodies are made up of individual cells, usually attached to each other but sometimes not – blood cells or sperm for example. They spend their whole life dividing and replacing themselves, and they are never static. Each cell has a nucleus where our DNA is stored. Cancer cells are different from normal cells, and they divide and replicate much more rapidly.

Radiation kills cells by damaging their DNA directly or creates charged particles (free radicals) within the cells that can in turn damage the DNA, but it does so far more in rapidly growing cells than in normal ones.

Cancer cells whose DNA is damaged beyond repair stop dividing or die. They are then broken down and eliminated by the body’s natural processes.

External beam radiotherapy uses high energy X-ray beams to treat prostate cancer. The X-ray beams are directed at the prostate gland from outside the body.

Radiotherapy treats the whole prostate, and sometimes the area around it. The treatment is painless but it can cause side effects.

You may be able to have radiotherapy if your cancer is contained inside the prostate (localised prostate cancer) or if your cancer has spread to the area just outside the prostate (locally advanced prostate cancer).

Radiotherapy can also be used after surgery if your PSA level starts to rise or if tests suggest that not all the cancer was removed.

Types of external beam radiotherapy

There are two types of external beam radiotherapy, 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) and intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT).

3D conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT)

With 3D-CRT, the radiation beams match the shape of the prostate as closely as possible. This aims to avoid damaging the healthy tissue surrounding it, reducing the risk of side effects.

Intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT)

With IMRT, the radiation beams are matched precisely to the size, shape and position of the prostate. The strength of the radiation beams can also be controlled so that different areas get a different dose. This means a higher dose of radiation can be given to the prostate, without causing too much damage to the surrounding tissue. The risk of side effects is usually lower with IMRT than with 3D-CRT.

Advantages of radiotherapy

- Many men are able to carry on with their normal day-to-day activities during treatment.

- Radiotherapy can be used even if you’re not fit or well enough for surgery.

- Radiotherapy is painless.

- Daily sessions only last 10 to 20 minutes each.

- You don’t need to stay in hospital.

Disadvantages of radiotherapy

- You will need to go to hospital five days a week for several weeks, which might be difficult if you need to travel.

- You can get side effects, such as bowel, urinary and erection problems, as well as tiredness and fatigue.

- It may be some time before you know whether the treatment has been successful.

- If you have radiotherapy as your first treatment and your cancer comes back or spreads, follow up surgery may sometimes not be possible.

What happens with radiotherapy

You may have hormone therapy before beginning radiotherapy. This shrinks the prostate and makes the

cancer easier to treat. At some hospitals, you may have three to four gold seeds, called fiducial markers, put inside your prostate. Each is about the size of a grain of rice. They show up on scans and help the radiographer see the exact position of the prostate.

Before starting radiotherapy you will have a planning session, where you will have scans of your prostate. In most hospitals small permanent marks (tattoos) are made on your skin. This helps the radiographers get you into the right position for treatment.

You will have one treatment (known as a fraction) at the hospital five days a week with a rest over the weekend. You can go home after each treatment. Radiotherapy usually continues for seven to eight weeks.

At the start of each session, the radiographer will help you get into the correct position – using the marks made on your body as a guide. The treatment then starts and the machine moves around your body. It doesn’t touch you and you won’t feel anything. You’ll need to keep very still, but the treatment only takes a few minutes.

It’s safe for you to be around other people, including children and pregnant women, during your

radiotherapy. The radiation doesn’t stay in your body so you won’t give off any radiation.

Follow up after treatment

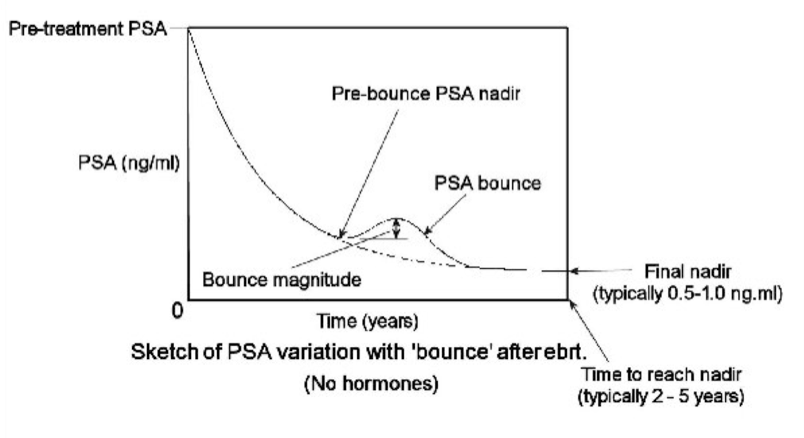

You will have regular check-ups after your radiotherapy. There is usually a PSA test a week before your check-up. After radiotherapy, your PSA should start to drop. Some PSA will still show up in tests because healthy prostate tissue will continue to produce PSA. How quickly your PSA level drops, and how low it falls, will depend on whether you had hormone therapy alongside radiotherapy.

You may see a rise and fall in your PSA level around one to two years after treatment. This is called ‘PSA bounce’. It is normal, and doesn’t mean your cancer has come back. A sign that your cancer may have come back is if your PSA level has risen by 2ng/ml or more above its lowest level, or if it has risen for three or four PSA tests in a row.

If your PSA level does rise, your doctor may check your PSA level for at least six months before deciding on further treatment.

Treatment options after radiotherapy

If the cancer does come back, there are further treatments that you may be able to have. Surgery is rarely an option because radiotherapy makes it very difficult to remove the prostate, and serious complications – principally urinary incontinence – are common.

Side effects of Radiotherapy

Like all treatments, radiotherapy can cause some side effects. These happen when the healthy tissue near the prostate is damaged by radiotherapy. Most recover so side effects usually only last a few weeks or months. But some side effects can start months or years after treatment. These may be similar to the side effects you had during or soon after radiotherapy and can last a long time.

If you have hormone therapy as well as radiotherapy, you may get side effects from the hormone therapy.

Side effects can include:

- Urinary problems: Radiotherapy can irritate the bladder and urethra and cause urinary problems, including needing to urinate urgently and more often and, sometimes, blood in the urine.

- Bowel problems: Radiotherapy can irritate the lining of the bowel and cause problems there – usually bleeding – but these usually improve once treatment has finished. Some men will find that their bowel habits change permanently.

- Tiredness and fatigue

- Radiation can leave you feeling very tired, especially towards the end of your treatment. It usually improves after your treatment but some men find it lasts longer.

- Sexual problems: You might get erection problems, and it can take up to two years for these to fully appear. You may not produce any semen after radiotherapy, and have a dry orgasm where you feel the sensation of orgasm but don’t ejaculate.

- Other problems

You may get other problems during or many years after treatment. These can include the following. - Lymphoedema – if your lymph nodes are treated, there is a slight chance that fluid might build up in your tissues. It usually affects the legs, but it can affect other areas, including the penis or testicles. It can happen months or even years after radiotherapy.

- Hip and bone problems – radiotherapy can damage the bone cells and the blood supply to the bones near the prostate. This can cause pain, and hip and bone problems later in life.

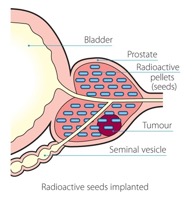

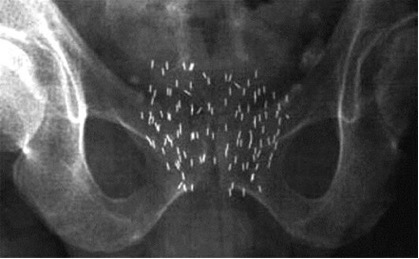

Permanent seed brachytherapy, also known as low dose-rate brachytherapy, involves having tiny radioactive seeds implanted in your prostate gland. Radiation from these seeds destroys cancer cells.

Who is suitable?

You may be suitable for this treatment if your cancer is thought to be contained within the prostate gland and:

- Your PSA level is 10ng/ml or less.

- Your Gleason score is 6 or 7 (3+4 or 4+3).

- The cancer staging is T1 – T2.

- Your prostate is not much enlarged.

Sometimes a medication called a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor may be given to shrink the prostate to make it suitable.

Brachytherapy may not be suitable if you have a very large prostate gland, have problems passing urine, or have recently had an operation called a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). Brachytherapy and TURP have an unacceptable risk of urinary problems.

Advantages

- You will be in hospital for just one or two days for the treatment itself.

- Recovery is quick. Most men can return to their normal activities a couple of days after treatment.

- The radiation is localised inside the prostate gland, so there may be less damage to the surrounding areas.

- There may also be less damage to the nerves that control erections than after other prostate cancer treatments.

Disadvantages

- Brachytherapy can cause side effects such as urinary, bowel and erection problems.

- It usually requires a general anaesthetic.

- It may be some time before you will know whether the treatment has been successful.

What happens with Brachytherapy?

What happens with Brachytherapy?

First you will have a planning session to measure the size and position of your prostate. This is to work out how many radioactive seeds you need. The prostate is mapped using an internal ultrasound probe, similar to the one used for your prostate biopsy. You may need a short general anaesthetic for this.

The radioactive seeds will either be implanted on the same day as the planning session (one-stage procedure) or they will be implanted two to four weeks later (two-stage procedure).

For the operation itself you will have a general anaesthetic, or less commonly a spinal or epidural anaesthetic.

The doctor puts 80 to 120 very small radioactive seeds into the prostate, using a fine needle inserted into your back passage. These seeds stay in the prostate and they release radiation slowly for a few months. Over this time only the prostate receives the high dose of radiation, and it does not travel elsewhere in the body. After a few months the radiation in the seeds fades away.

Unfortunately the urethra – the tube we pee through – runs down the central core of the prostate and some degree of radiation to it is unavoidable.

After seed implantation, you will have a low dose of radiation in your body for a few months. But by the time it reaches the outside of your body, the radiation dose is very small. So you don’t need to worry about being a danger to other people. It is perfectly safe to sleep in the same bed as your partner and to have sex.

Follow up

You will have a CT or MRI scan some weeks after the treatment to check the position of the seeds, and will have regular follow-up appointments to monitor PSA level and any side effects. If your treatment has been successful, your PSA level will drop, although it may start to rise again because your prostate will still produce some PSA. Some men may experience a rise and fall in PSA at around one to two years after treatment.

Side effects

You may not have any side effects for several days until the radiation from the seeds begins to take effect. Side effects are generally at their worst a few weeks after treatment, when the radiation dose is strongest, but should then improve over the following months as the seeds lose their radiation.

The most common side effects are:

- Blood-stained urine is normal.

- Discoloured semen for a few weeks.

- Bruising and pain in the area behind the testicles. This will gradually ease.

- Discomfort passing urine and needing to pass urine more often, especially at night, is to be expected. Up to 15% can’t pass urine at all and have to have a tube into the bladder (catheter) put in for a few days. This can be needed for up to a month.

- Other problems include ongoing difficulty passing urine, erection problems, bowel problems and tiredness.

- ‘Seed migration’, where seeds may leave the gland.

High dose rate brachytherapy (HDR) is only used alongside a course of external radiotherapy or hormonal therapy.

With HDR treatment a radiotherapy doctor puts thin tubes into your prostate through the skin behind your testicles while you are under an anaesthetic. These tubes contain a radioactive material that gives a high dose of radiotherapy to the prostate gland in a short time. With the advice of a computer program, when the correct dose is reached the doctor removes the radioactive tubes. So when you wake up, the treatment is all done. Residual radiation is quickly gone.

This treatment seems to be better at keeping localised prostate cancer under control than external radiotherapy alone. The survival rates appear to be higher and PSA levels are controlled in more men for longer. It is a new treatment and only available in some specialised centres.

Advantages

- Treatment in hospital with temporary brachytherapy takes just one or two days.

- It delivers a high dose of radiation direct to the prostate gland so healthy tissue nearby only gets a small dose of radiation and therefore is less likely to be damaged and cause side effects.

- Recovery is quick, which means you can usually return to your normal activities within a week of treatment.

Disadvantages

- It can cause side effects such as urinary, bowel and erection problems.

- You will need a general or spinal anaesthetic.

- You may need to stay in hospital overnight.

- It may be some time before you will know whether the treatment has been successful.

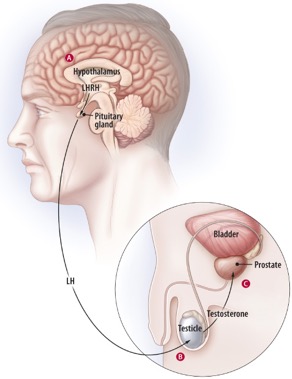

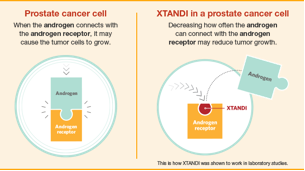

Hormone therapy works by stopping the hormone testosterone from reaching prostate cancer cells. It treats the cancer, wherever it is in the body.

Testosterone controls how the prostate gland grows and develops. It also controls male characteristics, such as erections, muscle strength, and the growth of the penis and testicles. Most of the testosterone in your body is made by the testicles and a small amount by the adrenal glands, which sit above your kidneys.

Testosterone doesn’t usually cause problems, but if you have aggressive prostate cancer, it can make the cancer cells grow faster. In other words, testosterone feeds the prostate cancer. If testosterone is taken away, the cancer will usually shrink, wherever it is in the body.

Hormone therapy alone won’t cure prostate cancer but it can keep it under control, sometimes for several years, before you need further treatment. It is also used with other treatments, such as radiotherapy, to make them more effective.

Who can have hormone therapy?

Hormone therapy is an option for many men with prostate cancer, but it’s used in different ways depending on whether or not your cancer has spread.

Localised prostate cancer

If you have localised prostate cancer, you might have hormone therapy alongside your main treatment, but it is unusual. Hormone therapy is not usually suitable for you if you’re having surgery, but can be used with radiotherapy.

Locally advanced prostate cancer

If you have locally advanced prostate cancer, you will usually be offered hormone therapy along with radiotherapy. Some men might have hormone therapy on its own if radiotherapy isn’t suitable for them.

Advanced prostate cancer

Hormone therapy will be offered as a life-long treatment for most men with advanced prostate cancer. It can control the cancer and manage symptoms such as bone pain. If the cancer comes back after treatment, hormone therapy will be one of the treatments available. It does not try to cure the cancer, but to contain it.

Types of hormone therapy

LHRH agonists

Luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists. These work by stopping messages (called Luteinising Hormone) from the pituitary, a part of the brain, that tell the testicles to make the testosterone hormone which prostate cancer calls need to keep growing. These medications are also called GnRH analogues.

They can only be given by injection. There are several different types. Some of the common LHRH agonists are:

- Goserelin (Zoladex)

- Leuprorelin acetate (Prostap)

- Triptorelin (Decapeptyl or Gonapeptyl).

Before you have your first injection of an LHRH agonist, and for a few weeks afterwards, you will be prescribed anti androgen tablets. This is to stop your body’s normal response to the first injection, which is to produce even more testosterone. This is called a ‘tumour flare’.

There is a slightly different injected hormone called Degarelix (Firmagon), which is described as a gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) blocker. It also works by blocking slightly different messages from the brain that tell the testicles to produce testosterone. You have it by injection just under the skin of the abdomen once a month. When you first start the treatment you have 2 injections on the same day. Degarelix does not cause a tumour flare response, so anti androgen tablets are not a necessity.

Tablets to block the effects of testosterone

Anti-androgens

Anti-androgens stop testosterone hormone from reaching the prostate cancer cells. They’re taken as a tablet. They can be used on their own or together with other types of hormone therapy.

Anti-androgens taken on their own may be less effective than other types of hormone therapy at controlling advanced prostate cancer. They are less likely to cause sexual problems and bone thinning than other types of hormone therapy.

There are several anti-androgens, including:

- bicalutamide (Casodex)

- flutamide

- cyproterone acetate (Androcur)

Duration of hormone therapy

If you have advanced prostate cancer, hormone therapy is likely to be a life-long treatment. Your hormone therapy hopes to keep your cancer under control for several months or years. But over time the cancer cells may change and your cancer might start to grow again. Also if you are having side effects, you might possibly be able to have intermittent hormone therapy. This involves stopping treatment when your PSA level is low and stable, and starting treatment again when your PSA starts to rise. Some of the side effects may improve while you’re not. However very few centres now recommend this.

If your cancer is no longer responding as well to one type of hormone therapy, it may still respond to other types of hormone therapy or a combination of treatments. And there are other treatments you might be able to have. These include chemotherapy, and new types of hormone therapy, such as abiraterone (Zytiga®) and enzalutamide (Xtandi®).

Side effects

Like all treatments, hormone therapy can cause side effects. It might seem like there are a lot, but you may not get all of them. Hormone therapy affects men in different ways. Some men have few side effects or don’t get any at all. These include;

- hot flushes

- changes to your sex life including loss of libido and erection problems

- tiredness

- changes to your mood

- bone thinning

- breast swelling and tenderness

There are treatments and support to help manage side effects. Some men find that they get better or become easier to deal with over time. The side effects are caused by lowered testosterone levels. They usually last for as long as you’re on hormone therapy. If you stop your hormone therapy, your testosterone levels will gradually rise and the side effects should improve.

How is my cancer monitored with hormone treatment?

By regular PSA testing, which can be done by your GP. If the PSA stays low, and if you are well and not experiencing any major side effects from the treatment, you will be followed up by your GP. You will be referred back to the hospital if;

- Your PSA starts to rise.

- Side effects are troublesome and not responding to treatment with your GP or nurse.

- If there is any worry that the cancer has spread, for example weight loss or bone pain.

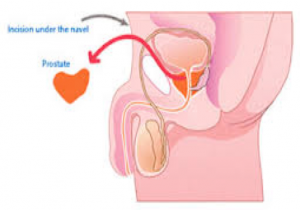

Surgery For Prostate Cancer

Surgery, a fairly major operation, is one of the main treatment options for prostate cancer. The aim of the treatment is to completely remove and cure the cancer. It is not suitable for every type of prostate cancer, or for every man with this cancer. This surgery is called Radical Prostatectomy. It involves removing the prostate and related structures, mainly the seminal vesicles and perhaps nearby lymph glands.

After the operation the removed structures are examined by a pathologist to check that all the cancer has been removed, and that enough normal tissue around the cancer has been also removed. This is termed ‘checking the margins’. If the margins are clear no further treatment is usually needed, but if it is found that the cancer involves any of the margins then further treatment may be indicated.

Which types of cancer are suitable?

Surgery is an option for men with cancer that is contained inside the prostate (localised prostate cancer) and who are otherwise fit and healthy. It may also be an option for some men with cancer that has spread to the area just outside the prostate (locally advanced prostate cancer). This will depend on how far the cancer has spread.

What men are suitable for surgery?

Because a radical prostatectomy is a major operation, we have to be fit enough for surgery. It may not be suitable for you if you have other significant health problems, you’re over 75 or you’re overweight. If so you’re more likely to have problems during and after surgery, and it may be too risky and some other treatment considered.

Types of Radical Prostatectomy

Radical Prostatectomy can be carried out in any one of three methods. The aim of each is the same – to remove the cancer in its entirety – and as far as we know all three have the same success rate. The methods are;

- Open prostatectomy.

- Laparoscopic prostatectomy (keyhole).

- Robot assisted keyhole prostatectomy, or ‘Da Vinci Prostatectomy’.

In Ireland, this is the most established and most frequently performed operation for prostate cancer. It is a major operation that takes about 2 hours to perform with a general anaesthetic, and is only done in hospitals. By far the most common method is called a Retropubic Prostatectomy, but rarely another method known as a Radical Perineal Prostatectomy is preferred.

Retropubic Prostatectomy

There is one 10-15cm skin incision, just above the area of the pubic hair, and this is termed a Retropubic Prostatectomy because most of the operation is behind and below the Pubic bone.

If there is a reasonable chance the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes (based on your PSA level, DRE, and biopsy results), the surgeon may remove lymph nodes from around the prostate at this time (known as a lymph node biopsy). The nodes are usually sent to the lab to see if they have cancer cells, which can take a few days to get results.

After the surgery, while you are still under anaesthesia, a catheter (thin, flexible tube) will be put in your penis to help drain your bladder. The catheter usually stays in place for 1 to 3 weeks while you heal. You will be able to urinate on your own after the catheter is removed.

You will probably stay in the hospital for a few days after the surgery, and your activities will be limited for about 3 to 5 weeks.

Radical perineal prostatectomy

In very rare cases, the incision is made in the perineum, the space between the scrotum and anus.

In this operation, the surgeon makes the incision in the skin between the anus and scrotum (the perineum), as shown in the picture above. This approach is used less often because it’s more likely to lead to erection problems and because the nearby lymph nodes can’t be removed.

This is often a shorter operation and might be an option if you aren’t concerned about erections and you don’t need lymph nodes removed. It also might be used if you have other medical conditions that make retropubic surgery difficult for you. It can be just as curative as the retropubic approach if done correctly. The perineal operation usually takes less time than the retropubic operation, and may result in less pain and an easier recovery afterward.

After the surgery, while you are still under anaesthesia, a catheter will be put in your penis to help drain your bladder. The catheter usually stays in place for 1 to 2 weeks while you are healing. You will be able to urinate on your own after the catheter is removed.

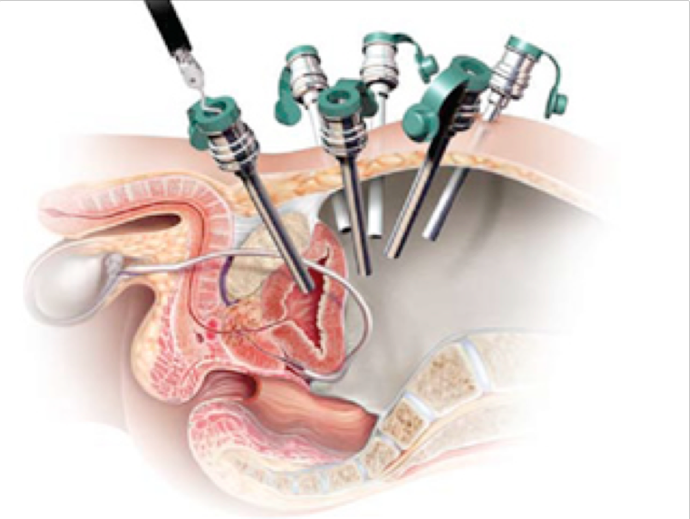

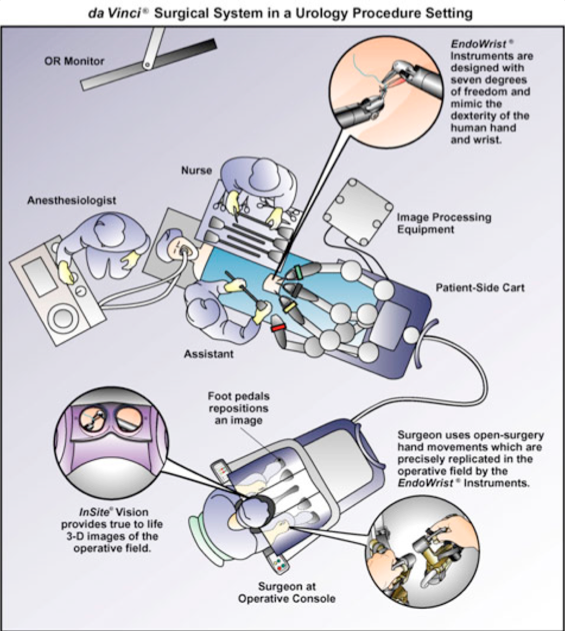

Here the surgeon, instead of standing beside the operating table, sits at a console away from the surgical field while an assistant works at the patient’s side. Up to seven small incisions are made in the patient’s abdomen, through which specialised instruments are inserted.

The surgeon views the procedure on a screen via through a camera with a binocular vision system, giving a three dimensional view of the operation. By positioning the camera close to the operative field, high magnifications can be achieved.

The surgeon controls the robotic arms and camera through a system of wrist controls and foot pedals. The robot instruments are designed to function in a manner similar to the human wrist, which allows complex maneuvers to be performed effortlessly. The system can be scaled up or down to facilitate complex microsurgical techniques.

Hand tremor is automatically eliminated by the system. The instruments may be quickly switched to enable different functions such as grasping, cutting, coagulating, and sewing. It is complex and fairly new surgery, and available in only a few hospitals. Overall success rate is the same as for the other two methods of operating, but there does seem to be less risk of side effects – mainly erectile dysfunction – and hospital stay is shorter.

Sometimes it is technically very difficult to continue through this operation, and the surgeon will need to take over and convert it to a traditional open prostatectomy. This is never known before the operation starts, but the instruments needed are always on standby.

Da Vinci surgery is possibly better at avoiding the very delicate nerves that run down each side of the prostate, and which are needed to achieve an erection. It depends on where in the prostate the cancer is situated. The surgeon will always attempt to avoid them, but it cannot be predicted in advance. This is termed ‘Nerve Sparing Prostatectomy’.

da Vinci vs. Open vs. Laparoscopy

The following table looks at patient outcomes following surgery for prostate cancer and compares “best in class” data from three types of surgery. As you can see, da Vinci Prostatectomy seems to show measurable advantages as compared to both conventional open surgery as well as conventional minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery.

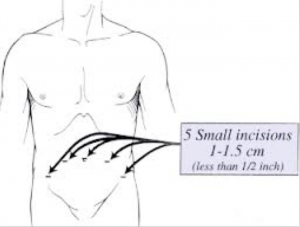

The word laparoscopy means to look inside the abdomen with a special camera or scope. Surgery performed with the aid of these cameras is known as keyhole or minimally invasive surgery.

Traditional surgery requires a 10-15cm incision (cut) down the centre of the abdomen and a lengthy recovery period. Laparoscopic surgery eliminates the need for this incision. As a result, you may have less pain and scarring after surgery, faster recovery, and less risk of infection.

Laparoscopy appears to treat the prostate cancer as effectively as surgeries done with a larger incision.

What Are the Advantages of Laparoscopy?

As is the case with other minimally invasive procedures, laparoscopic prostate removal has some advantages over traditional surgery:

• Laparoscopy can shorten your hospital stay to one or two days. About 50% of men are discharged one day after surgery. (The length of stay depends on how quickly you recover and the extent of the surgery.)

• There is less bleeding during the operation.

• You are less likely to need prescription painkillers after you leave the hospital.

• At your follow-up appointment 1-2 weeks after surgery the catheter draining your bladder will be removed if there are no signs of other problems. Occasionally, the catheter remains in place for another week, as with conventional surgery.

• About 90% of patients can return to work or resume full activity in only two to three weeks.

Am I suitable For Laparoscopic Surgery?

Laparoscopic surgery is suitable for you if you have prostate cancer that has not spread outside the prostate and is not very aggressive, as well as a PSA test less than 10. If you have had previous open or laparoscopic pelvic surgery, even for another reason you would not be eligible. You may not be eligible if you have a history of hormone treatment (androgen deprivation therapy), which reduces the size of the prostate tumour.

What Are The Side Effects?

Research so far shows that symptoms of incontinence and impotence are similar for both minimally invasive surgery and traditional surgery. Men usually return to normal urinary function within three months.

Because this technique is more likely to be nerve-sparing, a man’s postoperative sexual potency rate should be comparable to that of traditional surgery. However, laparoscopic surgery has not been in use long enough to truly assess whether it leads to higher rates of potency.

What Happens During Surgery?

The surgeon will place a small needle just below your belly button and insert it into your abdominal cavity. The needle is connected to a tube that passes carbon dioxide into the abdomen. This gas lifts the abdominal wall to give the surgeon a better view of the abdominal cavity once the laparoscope is in place. The surgeon will then be guided by the laparoscope, which transmits a picture of the prostate onto a video monitor.

Next, a small incision will be made near your belly button. The laparoscope is placed through this incision and is connected to the video camera. The image your surgeon sees in the laparoscope is projected onto video monitors placed near the operating table.

Before starting the surgery, the surgeon will take a thorough look at your abdominal cavity to make sure the laparoscopy procedure will be safe for you. If the surgeon sees scar tissue, infection, or abdominal disease, the procedure will not be continued.

If the surgeon decides the surgery can be safely performed, additional small incisions will be made, giving access to the abdominal cavity and pelvic lymph nodes.

What Happens After Surgery?

You can expect to follow a liquid diet at first, then gradually to eat solid foods. When you go home, you will follow a soft diet, which generally means no raw fruits or vegetables.

Nausea and vomiting commonly occur because the intestines are disturbed during anaesthesia and surgery.

You will be encouraged to get out of bed and walk as much as possible, starting the first day after surgery. You should steadily increase your activity after you go home. For six weeks after surgery, you should not lift or push anything heavy.

Laparoscopic surgery requires extra long and specialised training, and is currently only available in a few specialised centres.

Radical prostatectomy is a major procedure. It aims to remove and cure the cancer, but it is not without possible side effects. These include:

• Infection, bleeding, bowel or bladder damage, pain. This is the same as with all surgery in this area.

• After the operation, no matter which type, you will have a urinary catheter in place for up to 1-3 weeks.

• Urinary incontinence. This is common after the catheter is removed, 30-40% for 3 months, 5% for I year. Not always. Sometimes it never recovers, and an incontinence pad needs to be worn.

• Bladder infections can happen because of the catheter. They can usually be treated with antibiotics.

• Crampy lower abdominal pains from bladder spasm can sometimes happen. They can be treated with anti-cholinergic medicines.

• Sexual problems are unfortunately common. When we ejaculate semen on orgasm, most of it comes from the prostate itself and from the seminal vesicles, all of which are taken away during the operation. So, while we can still achieve orgasm, it will be a ‘dry orgasm’ where the same sensations are felt but no semen comes out. While this makes achieving a pregnancy next to impossible, few men considering radical prostatectomy would consider this a problem.

• Impotence. We need the delicate nerves that run down each side of the prostate to be able to achieve and maintain an erection, and these can be damaged during the surgery. All surgeons try to avoid them, nut it is not always possible. It can take anything from a few months to three years for erections to return to normal, and there are medications that may help. There is evidence that this is less of a risk with robotic surgery.

• There is a risk that the surgery was not judged totally successful. Positive surgical margin – this means an area right on the edge of the prostate contains cancer cells – may be reported from the laboratory. It suggests that some cancer cells may have been left behind. This might mean you’re more likely to need further treatment, either radiotherapy on its own or along with hormone therapy. This can be considered an advantage of surgery, where at least we have found out.

Main Points

• Open radical prostatectomy (ORP) has been considered the gold standard for the surgical treatment of localized prostate cancer; however, laparoscopic (LRP) and robotic-assisted prostatectomy (RALRP) have become standards of care at many centres worldwide.

• The emergence of RALRP made laparoscopic dissection technically easier. Minimally invasive incisions create less postoperative pain, reduce blood loss, and decrease hospital length of stay.

• ORP provides long-term oncologic control for up to 15 years. Surgeons who prefer an open technique claim the ability to alter surgical technique in real-time based on intraoperative visual and tactile assessment of tumour stage.

• Urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction are the 2 major concerns for patients after radical prostatectomy. Continence rate is reported to be between 90% and 92% after ORP, 82% to 96% after LRP, and 95% to 96% after RALRP. Data may suggest that RALRP has some advantages in recovery of potency over other RP techniques.

• LRP and RALRP are technically demanding, and both have a significant operator learning curve.

• RALRP is the most expensive to the hospital due to purchase of the robot, maintenance, and cost of operative equipment. Although economic considerations are vital, the advantages provided by robotic technology have the potential to minimize patient morbidity while improving both functional and cancer cure outcomes.

Advanced Prostate Cancer

This can be also called Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (CRPC) or Metastatic prostate cancer.

It is of two types;

• Rising PSA levels but no hard evidence that the cancer has spread.

• Proven spread elsewhere (metastasis) with or without rise in PSA.

Metastatic prostate cancer is cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, most commonly to lymph nodes or to bones.

It is sometimes possible to have metastases (cancer spread) present even when the prostate tumour is still very small. So even if the tumour appears to be very small, if a bone scan shows that there is cancer in the bones, the prostate cancer is termed to be at M stage (Metastasis). It will be treated as metastatic cancer and can often be controlled for several years with treatment.

- M staging – metastases (cancer spread)

- M0 – No cancer has spread outside the pelvis

- M1 – Cancer has spread outside the pelvis

- M1a – There are cancer cells in lymph nodes outside the pelvis

- M1b – There are cancer cells in the bone

- M1c – There are cancer cells in other places

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy works by stopping the hormone testosterone from reaching prostate cancer cells. It treats the cancer, wherever it is in the body.

Testosterone controls how the prostate gland grows and develops. It also controls male characteristics, such as erections, muscle strength, and the growth of the penis and testicles. Most of the testosterone in your body is made by the testicles, and a small amount by the adrenal glands which sit above your kidneys.

Testosterone doesn’t usually cause problems, but if you have aggressive prostate cancer, it can make the cancer cells grow faster. In other words, testosterone feeds the prostate cancer. If testosterone is taken away, the cancer will usually shrink, wherever it is in the body.

Hormone therapy alone won’t cure prostate cancer but it can keep it under control, sometimes for several years, before you need further treatment. It is also used with other treatments, such as radiotherapy, to make them more effective.

Who can have hormone therapy?

Hormone therapy is an option for many men with prostate cancer, but it’s used in different ways depending on whether your cancer has spread.

Localised prostate cancer

If you have localised prostate cancer, you might have hormone therapy alongside your main treatment, but it is unusual. Hormone therapy is not usually suitable for you if you’re having surgery, but can be used with radiotherapy.

Locally advanced prostate cancer

If you have locally advanced prostate cancer, you will be offered hormone therapy along with radiotherapy. Some men might have hormone therapy on its own if radiotherapy isn’t suitable for them.

Advanced prostate cancer

Hormone therapy will be offered as a life-long treatment for most men with advanced prostate cancer. It can control the cancer and manage symptoms such as bone pain. If the cancer comes back after treatment, hormone therapy will be one of the treatments available. It does not try to cure the cancer, but to contain it.

Types of hormone therapy

LHRH agonists

Luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists. These work by stopping messages (called Luteinising Hormone) from the pituitary, a part of the brain, that tell the testicles to make the testosterone hormone which prostate cancer calls need to keep growing. These medications are also called GnRH analogues.

They can only be given by injection. There are several different types. Some of the common LHRH agonists are:

• Goserelin (Zoladex)

• Leuprorelin acetate (Prostap)

• Triptorelin (Decapeptyl or Gonapeptyl).

Before you have your first injection of an LHRH agonist, and for a few weeks afterwards, you will be prescribed anti androgen tablets. This is to stop your body’s normal response to the first injection, which is to produce even more testosterone. This is called a ‘tumour flare’.

There is a slightly different injected hormone called Degarelix (Firmagon), which is described as a gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) blocker. It also works by blocking slightly different messages from the brain that tell the testicles to produce testosterone. You have it by injection just under the skin of the abdomen once a month. When you first start the treatment you have 2 injections on the same day. Degarelix does not cause a tumour flare response, so anti androgen tablets are not a necessity.

Tablets to block the effects of testosterone

Anti-androgens

Anti-androgens stop testosterone hormone from reaching the prostate cancer cells. They’re taken as a tablet. They can be used on their own or together with other types of hormone therapy.

Anti-androgens taken on their own may be less effective than other types of hormone therapy at controlling advanced prostate cancer. They are less likely to cause sexual problems and bone thinning than other types of hormone therapy.

There are several anti-androgens, including:

• bicalutamide (Casodex)

• flutamide

• cyproterone acetate (Androcur)

Duration of hormone therapy

If you have advanced prostate cancer, hormone therapy is likely to be a life-long treatment. Your hormone therapy hopes to keep your cancer under control for several months or years. But over time the cancer cells may change and your cancer might start to grow again.

Also if you are having side effects, you might possibly be able to have intermittent hormone therapy. This involves stopping treatment when your PSA level is low and stable, and starting treatment again when your PSA starts to rise. Some of the side effects may improve while you’re not having treatment, but it can take several months for them to wear off. Few centres now recommend this.

If your cancer is no longer responding as well to one type of hormone therapy, it may still respond to other types of hormone therapy or a combination of treatments. And there are other treatments you might be able to have. These include chemotherapy, and new types of hormone therapy, such as abiraterone (Zytiga) and enzalutamide (Xtandi).

Side effects

Like all treatments, hormone therapy can cause side effects. It might seem like there are a lot, but you may not get all of them. Hormone therapy affects men in different ways. Some men have few side effects or don’t get any at all. These include;

• Hot flushes

• Changes to your sex life including loss of libido and erection problems

• Tiredness

• Changes to your mood

• Bone thinning

• Breast swelling and tenderness

There are treatments and support to help manage side effects. Some men find that they get better or become easier to deal with over time. The side effects are caused by lowered testosterone levels. They usually last for as long as you’re on hormone therapy. If you stop your hormone therapy, your testosterone levels will gradually rise and the side effects should improve.

How is my cancer monitored with hormone treatment?

By regular PSA testing, which can be done by your GP. If the PSA stays low, and if you are well and not experiencing any major side effects from the treatment, you will be followed up by your GP.

You will be referred back to the hospital if;

• Your PSA starts to rise.

• Side effects are troublesome and not responding to treatment with your GP or nurse.

• If there is any worry that the cancer has spread, for example weight loss or bone pain.

Treatment options for men with prostate cancer that is no longer responding so well to first hormone therapy.

Abiraterone

Abiraterone is a hormonal therapy. It’s used to treat advanced prostate cancer that has progressed.

The male hormone, testosterone, helps prostate cancer cells grow. To produce testosterone, the body needs an enzyme called 17α-hydroxylase (CYP17). CYP17 is found in the testicles, adrenal glands and prostate cancer cells. Abiraterone works by blocking CYP17 so that testosterone can’t be produced in the first place.

Abiraterone is given to treat prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body (advanced prostate cancer). If you’re already taking a hormonal therapy your doctor may ask you to continue with your existing treatment while taking abiraterone. It is also usually given along with another hormone called prednisolone, which blocks most of the possible side effects of the drug.

Side effects include

• Abiraterone may cause a rise in blood pressure, which will be checked regularly. It’s important that you take prednisolone tablets to avoid this.

• Tiredness is a common side effect

• There is a risk of bladder infection.

• Changes to the normal rhythm of your heart. If this happens, it’s usually temporary and can be reversed with medication. Your heart function will be checked before treatment starts, and you will have regular blood tests to check a chemical in the blood called potassium.

Enzalutamide (Xtandi)

This is a new drug, taken in tablet form, for men with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. It does not aim to cure the cancer, but to prolong active life.

Possible problems

• It may cause seizures, and cannot be taken with a history of epilepsy.

• It is very expensive.